Written by: Schlese Castilla

maggie and milly and molly and may / went down to the beach (to play one day)

–ee cummings

In the United States, renewed interest in outdoor learning is flourishing as more parents and educators embrace a daring possibility: the natural world can be a remarkable classroom. While outdoor learning isn’t a new phenomenon, existing models of education and childcare that center nature continue to inspire parents and educators in the United States.

The benefits of outdoor learning are well documented, but the terminology used to describe the various educational experiences providing such wonderful benefits can sometimes be confusing. The following brief guide is meant to clarify important terminology about the educational experiences outdoor learning can offer, with two important caveats:

-

Terminology usage about outdoor learning isn’t universal or consistently applied. As a result, you may find some schools use the same terms in different ways (or even use different terms interchangeably). The language of outdoor learning can vary from school to school, locality to locality, and state to state. Keep in mind: in some instances, there are real differences in the educational experiences outdoor learning programs offer. Always take time to familiarize yourself with the specifics of a program you’re interested in.

-

Whatever the educational experience, outdoor learning focuses on a diverse set of activities that use nature as a tool for open-ended learning and play that also promotes physical, cognitive, socio-emotional, spiritual development and wellness. Nature, from that vantage point, can be an immersive classroom for the potential study of all subjects.

Let’s Get Started: Defining Basic Terms

Forest Days and Nature Days

Designed for students of all ages, public and private schools maintain Forest Days or Nature Days through weekly, purposeful encounters with nature on their school grounds or nearby green space. Forest Days and Nature Days usually exist as part of a traditional student learning experience.

Forest School

Forest school education takes place daily and exclusively in nature. Students attend school outdoors, even when there are seasonal and weather changes. In other words, students enrolled in forest schools do not use indoor classrooms (unless they need to shelter in extreme weather). Although the term “forest school” suggests the setting for learning should occur in a wooded area, this is not a hard and fast rule.

The term “forest school” is also the name of the learning theory that proposes how children in forest schools learn in nature: through self-directed unstructured play, self-directed hands-on experiential learning, safe opportunities for risk-taking, and instructional material provided by the natural setting of the school grounds or nearby green space. A forest school experience is also designed to build strong, one-on-one connections between teachers and each child. It is a living laboratory dedicated to the unique needs and strengths of each child. Forest schools follow a learner-led curriculum, though some may incorporate traditional curriculum or learning standards. In both instances, the natural world is a springboard allowing students to experience social-emotional, physical, language, and cognitive growth.

Note: The Forest School movement emerged in 1993 inspired by long-standing traditions of outdoor learning across Europe and the UK. The Forest School Association offers specific guidance around this experiential outdoor learning model.

Nature-based Education

Nature-based education (NBE) is a learning process that utilizes nature as a the basis for all learning. Nature is the object of study and is the learning environment. Materials and approaches are all focused on nurturing deeper connections with nature. NBE gives children an opportunity to experience nature as a doorway that facilitates learning while promoting a sense of responsibility for the environment and a sense of place in the natural world. Children attending nature-based programs generally spend up to 50% of their learning time outside (though it certainly can be 100%!). Outdoor learning may be in concert with traditional, indoor schooling in a classroom. There is an astounding range of NBE formats and settings, so one size does not fit all! The term nature-based education is a general umbrella term describing a wide range of learning experiences that take place in, with, or about nature.

Nature Preschool

Typically, nature-based preschools are licensed early childhood education programs for children ages 3-5. Most experts agree on these characteristics that define nature preschools: about 50% of each class is spent outdoors (sometimes more or less), learning is centered on nature themes and environmental literacy, and nature is infused into indoor classroom spaces as well. Nature preschools provide space for early childhood development while helping children build an environmentally conscious identity. Because they are usually licensed programs, there may be more emphasis on academic components of curriculum.

Place-based Education

Place-based education engages and introduces children to their local community and environment in order to teach a variety of subjects. Place-based education helps children forge deeper connections with and between the people and places that make up their community. It encourages an appreciation of the natural world with a focus on community, service, and local civic engagement. Place-based learning can occur in any environment, and has gained popularity because it allows students in urban settings to connect and learn in green spaces while developing their cognitive and socio-emotional skills.

Outdoor Preschool

Outdoor preschool is a broad term acknowledging the reality that immersive early childhood education nature programs do not have to take place in a forest. Outdoor preschools, in fact, can have a home-base at beaches, farms, parks, and deserts. Outdoor preschools are usually immersive, meaning they are outdoors 100% of the time, except to seek shelter during severe weather or emergencies.

Urban Forest and Nature Programs

Urban forest and nature programs demonstrate that nature is all around–and often closer and more convenient than a car ride to green space. Some urban forest and nature programs are situated in city parks. Other programs have creative ways of connecting with nature (gardens, urban farms, beekeeping, etc.) and bring the immediacy of nature to a child’s fingertips and imagination. Like place-based learning, urban forest and nature programs connect young learners from all socio-economic backgrounds to the wonder of nature in urban communities as they develop a respect for the environment and build a rich reservoir of cognitive and socio-emotional skills.

The Road Ahead

Already an inclusive educational phenomenon, as more students begin their outdoor learning journey, programs that are responsive and intelligently meeting the realities of student diversity (economic background, disability, language, race, LGBTQI+) are appearing on the horizon, too. To date, the number of forest and nature schools continues to grow. In 2021, the Eastern Region Association of Forest and Nature Schools offered professional development to teachers in all 50 states and 11 countries! Such unprecedented demand for nature-based teacher training may indicate a promising shift in how we think about learning and play.

Spotlight on Lingelbach Elementary School Forest Days Program, Philadelphia, PA

Written by: Susan Chlebowski and Brianne Good

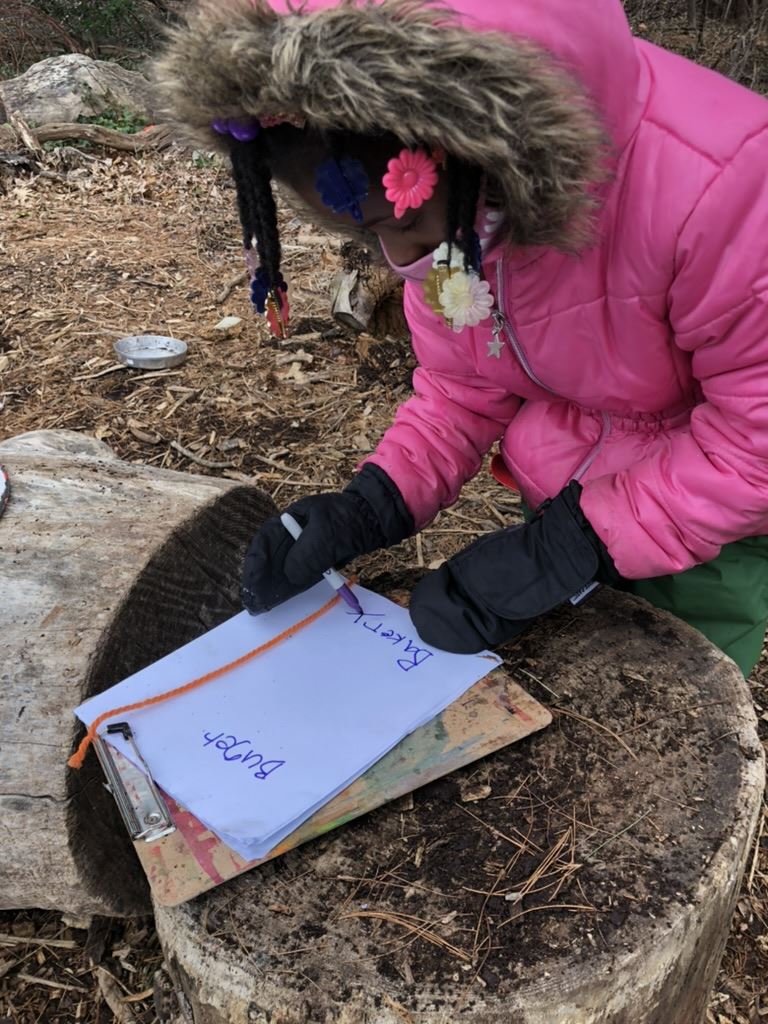

Imagine for a moment you are standing beside a brook after a long rain. The energy of that water is near to overflowing the banks, and anything in its path gets swept hurriedly down stream. This is the experience we have weekly with students at a public school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania as they pour from their classroom to our outdoor space on the school grounds. Each week, we spend two hours outdoors with a group of kindergarten or first grade students on their wooded, yet urban school campus, providing nearly 100 children with regular outdoor learning opportunities.

What have we noticed? These are highlights of what we are learning the children need from Forest Days:

F - freedom. The children crave freedom of choice, freedom of movement, and freedom to be themselves. This freedom shows up in their exuberant love of exploration, discovery, tree climbing and creative self-expression in our outdoor art areas.

O - outdoors. When outdoors, many of the children seem completely different. Quiet becomes loud, bold becomes shy, and outcast becomes friend. It is all welcome, and celebrated.

R - routine. We carry the same simple routine with us from week to week, and the children know and love that familiarity.

E - empathy. We are building empathy among the children, between the children and living creatures, and between the children and the earth.

S - safety. We hold a safe space for the children to learn, ask questions, and feel feelings.

T - time. Perhaps one of the most important pieces of the Forest Days model is simply the gift of time we give children to play, learn, wonder, explore, and be.

.png)